Germany will go to the polls on Sunday in what will represent the country’s most important set of elections since reunification. After 16 years in charge, Chancellor Angela Merkel will retire, leaving behind what is best described as a mixed legacy. Granted she represented a source of stability in what were often turbulent times in the eurozone, but those turbulent times were in many ways a function of her insistence on imposing austerity measures on periphery eurozone countries in response to the debt crisis in 2011/2012 and her refusal to back plans for the creation of a banking and fiscal union.

On the economic front, German GDP expanded by an average of 1.5% p.a. from 2005 to 2019 which was solid when compared to growth rates of 1.3% and 0.0% in periphery economies such as Italy and Spain. However, this represents a relatively large underperformance relative to the US, which grew by an average of 1.9% over the same timeframe. Merkel’s focus on fiscal restraint represented a major headwind on this front, with the government amending the constitution in 2009 to introduce a measure known as the ’debt brake’ that limited the government deficit in any one year to no more than 0.35% of GDP. For reference, between 2010 and 2019 budget deficits in the US averaged 4.8%.

A by-product of this German fiscal restraint has been a rise in inequality, with the share of income accruing to the top 10% of earners rising from 32.2% to 37.3% between 2000 and 2020 per the World Bank. Combined with the impact of Merkel’s decision to adopt an open-door policy at the height of the Syrian crisis in 2015 that led to the arrival of over one million refugees, this has seen support for populist parties such as the far-right Alternative for Germany (AfD) surge.

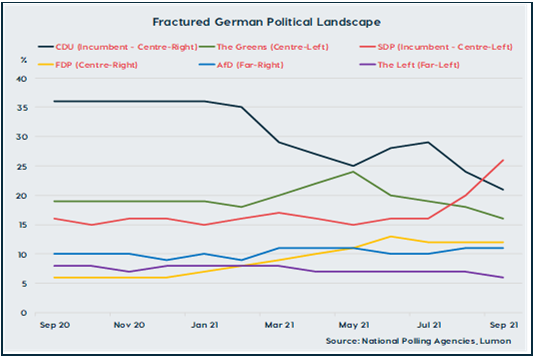

Similar to what’s occurred elsewhere in Europe, the German political landscape has become increasingly fractured. Previously, the Bundestag was dominated by Merkel’s centre-right Christian Democratic Union (CDU) and the centre-left Social Democratic Party (SDP), who tended to rule in coalitions with the centrist Free Democrats (FDP) and more recently the Greens. Indeed, before the 2017 contest, the CDU and SPD typically won 70=80% of the total vote share. Next Sunday, however, neither party is expected to win more than 25%. In addition to the AfD, we have also seen the emergence of the Greens as a real political force (polling at 16% vs circa 12% in 2017), while support has also held up for the far-left Die Linke (made up the remnants from the East German communist regime).

Owing to the increasingly crowded field, it is difficult to ascertain what the most likely outcome of this week’s election is. What the data does appear to suggest is that the government will not be led by the incumbent CDU, with Angela Merkel’s successor as party chief, Armin Laschet, wildly unpopular with the electorate. Laschet has been hurt by a series of gaffes, the most prominent of which saw him pictured laughing when inspecting flooded German villages in July, as well as his attempt to position himself as an agent of change when what the public wants is stability. This has been reflected in a late surge in support for the SPD, who had been written off as a spent force. Their lead candidate, Olaf Scholz, has presented himself as the true continuity candidate, having served as the Minister for Finance under Merkel’s last government as part of a grand coalition between the CDU and the SPD.

It is not clear who might join the SPD in power, though regardless of the outcome our base case is that it will not lead to any major changes in German economic policies given Scholz has framed his campaign around continuity. The new government will likely adopt a less restrictive approach to fiscal policy, with all parties highlighting the need to invest to improve Germany’s crumbling infrastructure, boost digital capabilities and prepare for climate change. However, Scholz has indicated that he is not in favour of reforming the debt brake so that such investments would not count toward the budget deficit. As such, those expecting a significant increase in government spending are likely to be disappointed, particularly given the fiscally hawkish Free Democrats will play an integral role in coalition talks.

Overall, we struggle to see the election having a meaningfully positive impact on the euro in the medium-term, outside of a shock left-wing coalition comprised of the SPD, Die Linke and the Greens. However, given current polling, it will take some time for a clear picture to emerge, with a period of extended coalition talks likely on the cards.

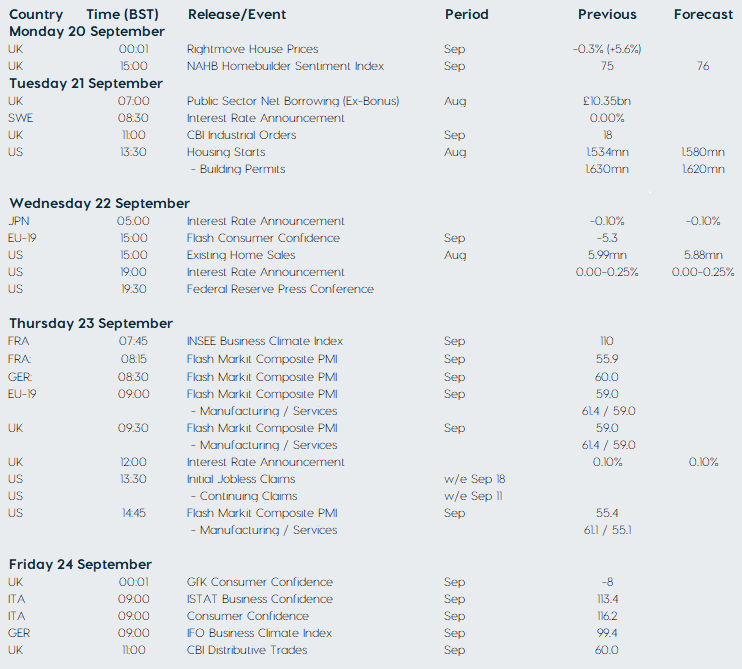

The Week Ahead

US

The highlight this week is the Fed’s September meeting, though no changes to the policy are anticipated. Over the summer, a series of strong non-farm payroll reports had led markets to question whether the central bank could announce a tapering of its asset purchase programme in September, given Chair Powell had tied the timing of such a move to an improvement in labour market conditions. However, soft employment data in August (non-farms +235k vs 975k average in June/July) appears to have delayed an announcement until Q4. Indeed, several of the more hawkish members of the Federal Reserve Open Market Committee (FOMC) advocated delaying acting given the slowdown in jobs growth and amid concerns that the delta variant may be meaningfully weighing on the economic rebound.

While a tapering announcement appears unlikely, the Fed could yet spring a hawkish surprise on markets through the release of their latest Summary of Economic Projections Attention will focus on the updated dot plot, which shows Fed officials’ view on the likely trajectory for the benchmark fed funds rate conditioned on their forecasts. Back in June when a majority signalled for the first time that they envisaged the tightening cycle beginning in 2023, we saw the dollar rally significantly in a move that pushed GBP/USD back below the $1.42 threshold. We note that it would require just two officials to move their ‘dots’ for the median view of policymakers to be for rate hikes in 2022, which would be consistent with our view and market pricing. In terms of the economic outlook, given recent supply-side developments we expect that the Fed’s growth forecasts will be revised somewhat lower, at least for 2021, with inflation also likely to be seen remaining well-above target through much of 2022.

UK

On this side of the Atlantic, the Bank of England (BoE) will also hold its September Monetary Policy Council meeting this week. No changes to policy are anticipated, reflecting the fact that it is an interim meeting with no press conference or Monetary Policy Report due. We do see an outside risk of the central bank voting to prematurely end its asset purchase programme (due to run until end-year), particularly given recent hawkish comments from BoE policymakers who have signalled that they are concerned that labour market shortages may persist for some time (in part due to Brexit, but also the pandemic), pushing wages and keeping inflation above its 2% target (3.2% year-on-year in August). Even if the BoE does not act, the voter breakdown on the decision will attract significant attention, with just one member of the MPC voicing their support for such a move back in August. Should there be an increase in the number of officials voting to remove policy supports, sterling could attract some support.

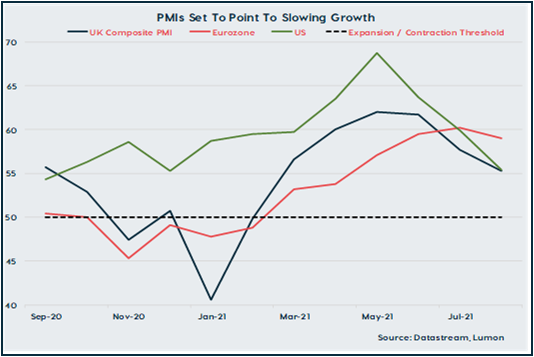

Data-wise, the flash Purchasing Manager Indices (PMIs), a closely watched measure of business activity, for September are also due this week. As school holidays have ended and workers have begun to return to the office, mobility levels have increased, and we anticipate that this will be reflected in a rise in the headline composite index. That said, we note that the PMIs relationship with economic activity has deteriorated since the pandemic has hit. For instance, while the economy effectively stagnated in July as the ‘pingdemic’ hit, the PMIs remained at a level consistent with strong growth in the month.

Eurozone

Over in the eurozone, there is a plethora of sentiment for September due this week. Of particular interest will be the composite PMIs, which are likely to point to a modest easing of activity as supply chain issues bite, re-opening effects fade, external demand begins to normalise (Europe is also particularly vulnerable to the slowdown in China) and the pandemic remains a headwind. This would be consistent with our view that activity in the eurozone peaked over the summer, with a gradual return to sluggish trend growth to be expected in the coming quarters.

Economic Calender

This blog post is intended to provide you with information on the services Lumon Pay Ltd (“LPL”) offer and should not be interpreted as advice or as a solicitation to offer to buy or sell any currency or as a recommendation to trade. Foreign exchange rates provided therein are for indicative purposes only and are not intended to give an accurate reflection of current currency exchange rates or to predict future movements in currency exchange rates. LPL, trading as Lumon, is a company registered in England with its registered address at Building 1, Chalfont Park, Gerrards Cross, Buckinghamshire SL9 0BG. LPL is authorised by the Financial Conduct Authority as an Electronic Money Institution (FRN: 902022).